Vehicles with large driver-side blind zones are much more likely to strike crossing pedestrians while turning left

Vehicles with large driver-side blind zones are much more likely to strike crossing pedestrians while turning left than those with small blind zones, a new study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety shows.

A large driver-side blind zone raises the risk of a left-turn pedestrian crash 70% compared with a small blind zone, the study found. Thick and slanted A-pillars, bulky side mirrors, and tall, long hoods all obstruct driver views. The field of view offered by the windshield, which alters the location of the blind zones, also affects the driver’s ability to see.

“These results clearly identify problematic aspects of vehicle design,” IIHS President David Harkey said. “The challenge for automakers will be to find ways to address them that don’t diminish the protection vehicles provide to their occupants in a crash.”

A grim trend

Pedestrian deaths have soared 78% since hitting their low point in 2009 and now account for more than 7,300 crash fatalities a year. Higher vehicle speeds and vehicle-centric infrastructure designs are among the likely culprits in the increase.

The trend toward vehicles with taller, blunter front ends — especially SUVs and pickups — is another suspected factor. These vehicles are more likely to injure and kill pedestrians when crashes occur. In addition, they are at a higher risk of hitting pedestrians while turning.

In the current study, IIHS researchers revisited turning crash risk, examining the influence of blind zones and other design elements that affect the driver’s ability to see.

Using a camera-based technique developed by Institute engineers, the researchers measured the blind zones of 168 vehicles from the vantage points of an average-size man and a small woman. The two heights correspond to the size of dummies commonly used in crash tests and represent a wide range of the driving population.

Because designs don’t change every year, the measurements applied to many make, model and model year combinations, allowing the researchers to analyze a large volume of pedestrian crashes involving these vehicles.

For a 5-foot-9-inch driver, cars had the largest driver-side blind zones on average, while pickups had the smallest. However, the windshields of pickups and SUVs generally provided a tighter field of view. The nearest visible point on the ground in front of these vehicles was also farther away.

For a 4-foot-11-inch driver, SUVs and pickups had the largest average driver-side blind zones. SUVs and pickups also provided the narrowest field of view and had the greatest distance to the nearest visible point.

Across all vehicle types, the average driver-side blind zone blocked 27% of the area to the left and front of the vehicle for a 5-foot-9 driver. For a 4-foot-11 driver, the average blind zone blocked 33%.

The average windshield afforded an 88-degree field of view for drivers of either height. The nearest visible point on the ground was 26 feet ahead for the taller driver and 30 feet away for the shorter one.

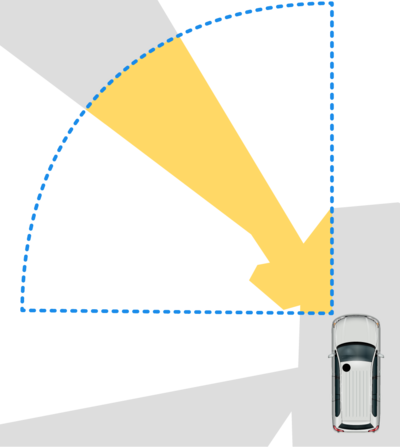

Using the measurements for the 5-foot-9 driver — representative of a broader population than the 4-foot-11 driver — the researchers defined blind zones that blocked more than 30% of the driver-side view as large. They categorized those that blocked 20%-30% as medium. Under 20% was small.

Blind zones and turning crashes

An analysis of nearly 4,500 police-reported pedestrian crashes in seven states showed that large driver-side blind zones were associated with a 70% increase in the risk of left-turn crashes with pedestrians, compared with small ones. Medium driver-side blind zones were associated with a 59% increase in left-turn crash risk.

To reach this estimate, the researchers counted how many times a vehicle in each of the three blind zone categories (small, medium and large) hit a pedestrian while turning left and how many times a vehicle in the same group hit a pedestrian while going straight. They then compared the ratios of left-turn to straight-moving crashes for each group.

Straight-moving crashes were included to help account for how often vehicles encounter and hit pedestrians, independent of driver-side blind zones.

A similar analysis of 3,500 crashes showed that passenger-side blind zones had no significant impact on the risk of right-turn crashes.

The location of the driver-side blind zones was also important.

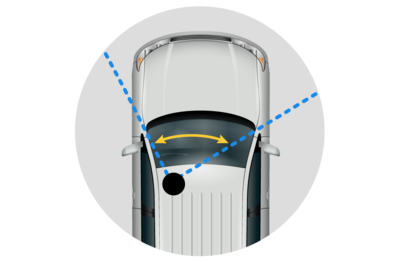

A front field of view of 85 degrees or less was associated with a 51% increase in left-turn crash risk versus a front field of view wider than 90 degrees. A narrower field of view moves the A-pillars and side mirrors forward relative to the driver’s line of sight, so they block more of the area in the vehicle’s path.

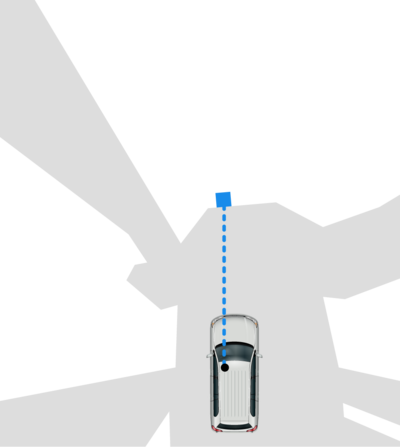

A nearest ground-level visible point more than 30 feet from the driver was associated with a 37% increase in left-turn crash risk. When the nearest visible point is farther away, more of the blind zone is directly ahead of the driver.

“When a driver’s view is partially blocked, it’s easy for a person in the crosswalk to disappear from sight,” said Wen Hu, senior research transportation engineer at IIHS and lead author of the study. “That’s exactly the kind of situation that leads to turning crashes.”

Key metrics for left-turn pedestrian crash risk

(shading depicts areas obscured for driver by vehicle components)

A challenge for designers

Some of the same vehicle characteristics that increase the size of blind zones make vehicles safer in other ways, so optimizing both aspects of design will require careful consideration. Thick A-pillars, for example, contribute to roof strength, protecting occupants in rollover crashes, while long hoods are related to the larger crumple zones needed to manage the forces of frontal impacts.

However, other types of changes addressing visibility or pedestrian safety would not affect vehicle structure. Side-view cameras could compensate for blind zones that cannot be eliminated. Hood airbags could reduce the likelihood of serious injuries, and pedestrian automatic emergency braking systems could be designed to function better while the vehicle is turning.

Changes to roads and crosswalks could also make a difference. Traffic lights can be set to allow pedestrians a few seconds to begin crossing before the light turns green for vehicles, for example. This allows drivers to see there is someone in the crosswalk before they begin to turn. Curbs can also be extended into the roadway at intersections. This puts waiting pedestrians in the driver’s line of sight and shortens the time that pedestrians are in the crosswalk.

“The driver’s ability to see is a fundamental element of safety that hasn’t received enough attention,” Harkey said. “That should change with our new ability to easily measure vehicle blind zones and assess their effects on crash risk.”