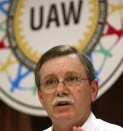

UAW's Gettelfinger Ready For Tough Negotiations

|

DETROIT, July 30, 2007; Jui Chakravorty writing for Reuters reported that in the build-up to crucial contract negotiations with the Detroit automakers, United Auto Workers President Ron Gettelfinger had taken to saying the union faces a crisis unlike anything in its 72-year history.

But with the talks now underway, analysts say negotiators across from Gettelfinger also face a different kind of UAW leader -- one who combines the traditions of the industrial union he represents with a new flexibility at the bargaining table.

Gettelfinger, 62, has surprised many with a willingness to work with big-money interests, including Wall Street advisors and private equity investors, in a bid to transform a struggling industry and preserve jobs.

While those traits have prompted some griping from disgruntled rank-and-file auto workers and retirees, Gettelfinger's biggest test comes now as he squares off against General Motors Corp, Ford Motor Co and soon-to-be private Chrysler.

The Detroit automakers want deep concessions as part of a bid to rebound from a combined loss of some $15 billion last year and keep jobs and production in the United States.

"Ron is the man of the hour. He's got the most difficult negotiation we have seen," said Dave Cole, chairman of Center for Automotive Research, which draws some funding from the industry.

In the eyes of some critics, the UAW -- like the industry it represents -- has been a victim of its own past success.

Since its first Depression-era sit-down strikes, the UAW has won solidly middle-class benefits for its blue-collar members -- from overtime and paid holidays to job security and some of the richest pensions and health-care packages in corporate America.

The concessions being sought now by the auto companies -- including more flexible work rules, permanent plant closures and changes to health care -- would have to be ratified by UAW members, long used to pay and benefits seen as the "gold standard" for organized labor in the United States.

At the current scale, U.S. auto workers command hourly wages and benefits of some $73 per hour. Wages alone are nearly $26 per hour, well above a manufacturing sector average of $17.

Analysts say Gettelfinger faces pressure to craft a compromise that is seen as giving away just enough to nudge the automakers out of financial crisis and save union jobs.

Gettelfinger himself has said the union is not in a "concessionary mode," but has declined to comment specifically on any of the hot-button issues on the table ahead of the Sept. 14 expiration of the UAW's current four-year contract.

"He knows how to put together a compromise. I cannot think of a better person to lead talks that will be nothing short of historic," said Gary Chaison, a professor of industrial relations at Clark University in Massachusetts.

BROTHER RON

Silver-haired, trim and an impassioned critic of the Bush administration, Gettelfinger can be combative and dismissive of parties he sees as outside the industry, including Wall Street and the media.

People who interact with him often say he is a serious man, who seldom jokes. In public meetings, he calls UAW colleagues "brother" and "sister," underlining the union's tradition of solidarity.

He also shuns alcohol, travels without an entourage and has banned staffers from golfing with management counterparts on union time to avoid the appearance of a too-cozy relationship.

Gettelfinger, who started his career in 1964 at a Ford assembly plant in Louisville, Kentucky, rose from the plant floor as a chassis line repairman to become regional director of the union.

He took night classes to earn a degree in accounting from Indiana University and rose to the position of head of the union's Ford department in 1998 before succeeding the late Stephen Yokich as UAW president in 2002 -- just as the U.S. auto industry started to slide into crisis.

In 2003, during the last round of contract talks, Gettelfinger and the UAW agreed to job cuts, plant closures and modest wage increases to protect relatively generous health care and pension packages.

But at the time, the Detroit automakers had almost 58 percent of the U.S. vehicle market, a share in danger of falling below 50 percent this year.

For that reason, the UAW faces pressure for further cuts, especially at Ford, which expects to burn through at least $15 billion before returning to consistent profitability in 2009.

After bringing in investment bank Lazard as an adviser, Gettelfinger negotiated mid-contract concessions with GM and Ford in 2005, which saved the automakers billions of dollars by shifting some health care costs to retirees.

The UAW has declined to say whether it will bring back Lazard to examine one of the most complex set of issues in the current talks: whether the union should agree to allow the automakers to set up a trust fund in exchange for wiping over $90 billion of unfunded retiree health care liabilities from their balance sheets.

Gettelfinger's approach has cost him some criticism.

After railing against financial buyers such as Cerberus Capital as "strip-and-flip" players, Gettelfinger stunned analysts and some of his own membership by backing the Cerberus purchase of Chrysler Group.

"That was probably one of the biggest flip-flops in corporate history," said Richard Caires, advisor to a group of UAW workers at Chrysler's Toledo, Ohio Jeep plant who had tried and failed to get a hearing at Daimler for a proposed employee buyout of Chrysler.