TYRANNOSAURUS WRECKS

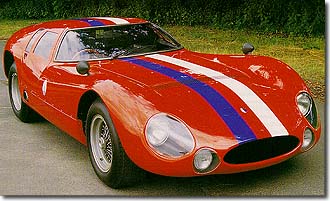

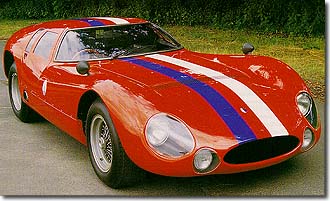

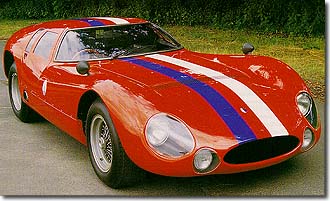

Marc Sonnery writes of the Tipo 151, Maserati's last great racing car and a pioneer in the design of the GTs. Photos by the author.

While material on Ferrari appears inexhaustible, quality information on Maserati is incomparably harder to find-an enticing paradox if you consider that in 1898, as you-know-who was just being born, Carlo Maserati was already tinkering with his first cycle engine a mere cannon-shot away. In turn, the few good Maserati books extant give little if any space to our subject, which is one of the most exciting racers ever born at Viale Ciro Menotti. In the early '60s, this car seemed poised to vault Maserati into that position of racing dominance it so frequently approached and so seldom achieved. The story of the promising Tipo 151-and of 151/3 in particular, the best, last, and most notorious of the line-is little-known but fascinating.

Even though Officina Alfieri Maserati had long ago been sold by the founding Maserati brothers, a continuity of engineering spirit remained in the form of Guerrino Bertocchi and Giulio Alfieri, both by this time pillars of the factory. Although most of the firm's efforts were smallish, well balanced machines, Maserati also occasionally generated a monster in its midst. Before the war there had been successful V16s and even an experimental V32. Postwar, the 1956-58 Tipo 450S, its 4-cam, 4.5-liter V8 credited to Colombo but penned by Taddeucci, was the factory's most fearsome creation.

As was typical of its day, most 450S chassis were clothed in minimalist barchetta bodywork, à la Ferrari Testa Rossa or Aston Martin DBR1. But an experimental 450S coupe, designed by English aerodynamicist Frank Costin and hurriedly built by Zagato, raised some very interesting questions. At Le Mans '57, the coupe showed the potential for blinding speed despite its grossly underdeveloped state. Though badly ventilated and aerodynamically unstable, the big GT easily ran at the leaders' record pace for the first two hours. This certainly left a sense of unfulfilled potential at Maserati, but since a 3-liter limit on sports-racers came into effect the next year, the 450S became a white elephant in Europe. The big V8 spyders did go on to notable success in America, and the engine spawned a roadgoing relative, the 5000GT.

But Costin's big-engine/low-drag concept got a new lease on life when Le Mans' sanctioning body, the ACO, created the Experimental Class for 4-liter cars in 1962. Taking advantage of this opportunity, Ingenere Alfieri created a 3943cc version of the 5000GT's V8 and shrink-wrapped it inside a dramatic enclosed body inspired by the 450S coupe. This car, the Tipo 151, also benefitted from the success of Maserati's Birdcages, which taught the firm much about lightweight spaceframe construction techniques.

Technology and experience weren't the problems, however-financing was. This, Alfieri believed, was solved when American Colonel Johnny Simone ordered one Tipo 151 (s/n 002) and Briggs Cunningham asked for two more (004 and 006). Minimal development-there was rarely any other kind at Modena-took place in the spring of 1962, with Bertocchi at the wheel as customary. The 151 was still unready when April's Le Mans test day rolled around, so when the coupes arrived at scrutineering the following June, they were totally unknown quantities. This relative and all-too-typical lack of testing would prove costly, but Maserati operated its campaigns on what it had available. By '62, that was little indeed.

On the other hand, all the omens looked good. Maserati had taken its best finish ever at Le Mans just the year before, with Augie Pabst and Dr. Dick Thompson holding onto fourth in their ailing Tipo 63, a rear-engined Birdcage entered by the Cunningham team. The same race had seen other Tipo 63s pedaled by Vaccarella/Scarfiotti (for Scuderia Serenissima) and Hansgen/McLaren (Cunningham), both of which had shown even more speed than the sole survivor. Thus encouraged, Maserati's 1962 entrants looked longingly at the winner's balcony.

No one stared more keenly than Johnny Simone. A former US Air Force pilot who had raced Jaguars and Maseratis, he had recently teamed with Paris distributor Jean Thepenier to become the Maserati importer for France. Business sense and enthusiasm dictated a racing campaign to go along with this new franchise, and Le Mans was the logical venue.

The Tipo 63s had been fraught with practical problems, and Cunningham's experience gave him a biting lack of faith in the subsequent 151. Johnny Simone, on the other hand, was convinced of the design's potential. In truth, we owe the whole saga of the 151s to this man, as for better or worse he carried this car on his back. Simone had to push Alfieri and Bertocchi to make time for the project-not an easy task when the factory's interest in racing had very much declined, but he was a man who never shrank from a high-maintenance project. His wartime career, his driving, and even his choice of a wife-the actress June Astor-proved that. Simone, however, was not the only one who had recognized the earlier 450S coupe's promise. While no one involved with the coming GTs from Ferrari or Aston Martin ever gave it credit, it's unthinkable that as everyone struggled with the same demons of drag and lift, Maserati's 1957 solution went unnoticed.

Toward mid-June of 1962, all the players converged on Le Mans, the 151's first race and the only time all three examples competed together. The red Maserati France entry owned by Simone, s/n 002, was entered for Trintignant and Bianchi; Cunningham's 004 and 006 chassis, both in white with blue stripes, would be handled by Walt Hansgen teamed with Bruce McLaren, and Dr. Dick Thompson paired with Bill Kimberley.

Thompson qualified his 151 in third position, four seconds behind Phil Hill's pole in a Ferrari 330LM-not a great differential considering the 8-mile course length. McLaren secured fifth and Trintignant eighth. This certainly got the attention of the opposition, and as the field took off, so did the Masers' earsplitting howl and impressive speed. All three cars ran right up with Maranello's far-more-tested fare, if not threatening the leading (eventually winning) Gendebien/Hill Ferrari, at least hounding it.

Thompson and Kimberley stayed in the top three during the early going, even briefly taking over second place before dicey handling and insupportable tire wear caused repeated pitstops and dropped them a half-dozen positions. These same Americans yo-yo'd back into third by 8:00 pm, but their problems soon returned, eventually resulting in Thompson leaving the road for good at Tertre Rouge.

Maserati France's car was in the thick of it, too. Trintignant, who'd never even sat in the 151 before, held fourth place at the end of the first hour-but there was a problem. "Oh, it held the road, yes," the driver recalls today. "It held the whole road!"

The trouble lay in Maserati's de Dion rear axle. "In a righthand curve, for example," Trintignant continues, "the left rear wheel would stay in line but the right wheel would toe out. This meant it wore down tires far too quickly, and we had to pit every ten laps to change them." This was exactly the same problem that felled Thompson and Kimberley, and after considering the ultimate result of that flaw-a crash-Simone withdrew Trintignant's entry "for safety reasons" in the tenth hour.

The second Cunningham entry ran as high as second and registered the highest official speed of the year (178+ mph), but this entry, too, suffered the problems of its brothers. Drivers McLaren and Hansgen struggled on past the halfway mark, borrowing tires wherever they could find them, only to retire just before dawn with engine problems. For Cunningham, it was one more frustrating example of an undeveloped car from Maserati; to Simone, the 151 was a promising horse only in need of a taming.

After Le Mans, both of Cunningham's 151s were sent to America. Oddly enough, their problematic rear suspensions were never seriously altered, although both did get a new clamshell nose in place of the original small engine lid. This no doubt eased the modifications made to one of them, which first received a 5.7-liter Maserati marine V8 and later a 7-liter Ford before being destroyed during testing at Daytona in early '63.

A few months later, the second car caught the eye of two men while being stored in New York. Businessman Chuck Jones and the talented Skip Hudson, a very fast racer in his own right, decided that the unloved 151 was exactly the car they needed. "We saw it kind of lying around in their workshops," Hudson remembers, "and just felt it would be fun to drive. And, yes, collectible too, though that wasn't a common thought at the time. Afterward, I drove it at Bridgehampton. It was very fast-a beast. The problem was that it didn't have enough grip with those fairly skinny tires, maybe six inches wide in front and seven in back. Even so, I still thought it handled pretty well, despite the de Dion. But it was obviously a car designed for a high-speed place like Le Mans, not for our type of tracks.

"We painted it dark red, which suited it well, and I raced it at Riverside, Elkhart Lake, and Goleta. I remember that last one particularly well, because the car was so hot inside that I just took the doors off and raced it like that...and came in second anyway! As for the lack of grip, well, I wasn't timorous-I just dirt-tracked it. In fact, when I had the car up at my place in the orange groves near Lake Matthews, one of those reservoir lakes above LA, I used to take it out at 6:00 a.m. and practice on the 13-mile road that went around the lake. That early there was nobody around to be scared by its great huge noise. Of course, it did startle people when once in a while I took it to the dairy to pick up some milk...! I even did a promo for Sears-Roebuck with the car, which was pretty uncommon at the time; I signed something like 5000 autographs."

On the other side of the Atlantic, Colonel Simone had outlined a series of modifications for s/n 002 to be carried out by Alfieri and tested (though again not enough) by Bertocchi. First, the 4-liter V8 was replaced by a thundering 4.9, allowed in '63 under the ACO's new GT rules (as a derivative of the roadgoing 5000GT). Then the problematic de Dion rear suspension-a special sliding-mount design which might have worked given major development-was dropped in favor of an expedient standard de Dion. At Le Mans' April test days it was Frenchman André Simon-no relation to Simone-who exercised the car.

A very quick and famously taciturn man, André Simon justifiably felt that luck had eluded him during his career. He had just won the 1962 Tour de France, but by and large his career had been punctuated by bad breaks. ("I remember him as very likable," Trintignant recalled recently, "but a bit of a savage-a recluse.") In any case, upon the driver's assessment, a number of further mods were carried out in the two months before the '63 running of the 24 Hours. By the time the race came around, fuel injection had replaced the 4-liter's carbs, allowing a lower and smoother hoodline, and the previous year's side exhausts had been encased within the body for less drag. New vents and intakes were installed with a close eye to airflow, and the oil coolers were moved from the tail to the nose.

Thus the 151, resplendent in red with patriotic white and blue stripes, was now quite a different machine than the one presented to the scrutineers in 1962. Singularly unimpressed, les Commisaires summarily ordered that the undersized side windows be enlarged. In retrospect, it was obvious that the greenhouse would never pass muster as presented-a mistake indicative, perhaps, of rushed preparation in Modena. But car owner Simone had kept the faith, and it's easy to see why. "The 151 was a car that, given the right conditions and attention," Skip Hudson remembers, "could really have done the job. Maserati had done very well with the Birdcage, and they could have really gotten it on with this car. Basically, they got screwed up."

Trintignant's opinion is less colorfully presented, but it echoes exactly the same thoughts: "If it had been properly developed, (the 151) could have had exceptional results. Maserati was motivated-there simply wasn't any money to work with."

After qualifying a satisfactory fifth, behind three Ferrari prototypes and an Aston DP215, the lone 151 featured even more strongly in '63 than it had the year before. Joining André Simon in the cockpit was America's Lloyd "Lucky" Casner, an ex-Air Force pilot like Simone and well known for the winning ways of his own CAMORADI team's Masers.

Picture the bright and sunny scene of the 151's greatest moment: In front of the packed grandstands, André Simon is uncharacteristically hopeful and feels ready for the sprint to the cars. A pompous official drops the flag, and 49 drivers dash across the tarmac. Simon reaches the Maser, and...the door is stuck closed! Adrenaline spurting from his ears, Simon yanks again harder and the recalcitrant portal pops open and smacks him in the face as the rest of the field roars away! Nose bleeding, badly delayed, and hotter than a jalapeño, Simon finally blasts away, flooring it through Tertre Rouge and onto Mulsanne Straight.

At the front of the pack, leader Pedro Rodriguez (Ferrari 330TRI) has Phil Hill (Aston DP215) hot on his heels. Then Hill squeezes by under braking at Mulsanne Corner and John Surtees (Ferrari 250P) jockeys in for advantage.

But every driver behind this flying trio had just perceived a steaming red blur blowing past them on the Straight, running as if hounded by all the demons of hell. It was Simon, shattering records and furious, and after overwhelming Surtees at Maison Blanche he faced a clear road ahead.

As tens of thousands rose to their feet for the end of Lap One, the loudspeaker blurted the news: "Mesdames et Messieurs.... C'est incroyable.... La Maserati est en premiere position!" André put the pedal down and let the 151 do what it did best.

"Incredible" was the word alright, and not only to the fans and Simone but particularly to the opposition. There was nothing that Surtees and Rodriguez could do but follow La Maserati in amazement for an entire hour. It was 15 laps before Surtees finally managed to get by, but Simon led again briefly during pit stops. Shortly before six in the evening, the Frenchman pit to let Casner have his turn; the American, too, was capable of leading in the Maser.

Alas, shortly before seven Casner crawled back to the pits, the transmission stuck in second gear with a reluctant shift fork. Bertocchi got busy, but the proper 2-hour repair was out of the question; lead driver Simon just told him not to bother. Had the problem been the price of excessive speed? Another Maserati development blunder? Or had Casner fumbled a downshift, as hinted at by André? Impossible to tell-all that is certain is that the biggest gun of Le Mans '63 was officially retired by Johnny Simone in the fourth hour. In gentlemanly abnegation, the Colonel expressed his complete satisfaction with his drivers' work, and vowed to be back.

There were more races for s/n 002 that year-a crash at Reims; first in class and eighth overall at Auvergne; a brake-smoking finish at Brands Hatch. Still, there was only one venue where the big, fast, and slippery Tipo 151 could truly feel at home: Le Mans. Johnny Simone knew it. In fact, he counted on it.

During the winter of 1963-'64, the purposeful and aggressive body of the standard 151 was replaced with a scientifically radical shape known retrospectively as 151/3. Willed into existence by Simone and transformed under Alfieri's guidance, 002's chassis was now lengthened two inches and its tracks slightly widened. Then a long, smooth, flat-deck body intended purely for top speed was hammered into shape by the skilled hands at Drogo, and on mating the two, Maserati's last front-engined true racer was born. Baptized the Tipo 152, the appellation 151/3 took hold instead for the very simple reason that it sounded better. Theoretically, the latest 5-liter engine and very slippery shape would allow a top speed of 200+ mph.

After a typically Modenese shakedown, the 151/3 was taken to Le Mans for test day. There the scrutineers objected to its tiny rear "mail-slot" window, and when the car was taken back to Italy the offending window was enlarged into the roof. Bertocchi then tested it on the Modena-Bologna autostrada, flirting with the promised 200 mph (198, to be exact) and no doubt grinning bullishly.

A further test with Simon at Monza on 21 May was no grinning matter, however. Accelerating out of the parabolica onto the main straight at 160 mph, the right rear wheel departed from the car and Simon spun violently. Thankfully, the vast width of the track allowed him to scrub off considerable speed before the inevitable impact, but this still threw André from the car, bleeding and shaken. The crash, Simon theorized, might have been caused by a loose spoke or a puncture. Something, in any case, was still amiss in the wheelarch....

With driver and car more or less healed in just over three weeks, the doctors cleared the one and the scrutineers the other for the '64 running of Le Mans. At almost 2400 pounds the 151 was now some 220 pounds heavier than before, but its 5-liter engine made 430 bhp @ 7000 rpm.

This year's entry would be co-driven by the returning Trintignant, but with the car barely rebuilt, official practice for Le Mans became a shakedown run for the Maser. The front tires were soon shown to be touching the wheelarches, so Simone's men fruitlessly hammered away at them NASCAR-style. Further time was lost in properly resetting the suspension, and the result was a disappointing 15th place in qualifying.

This year, Trintignant's careful startup procedure again saw the 151 coming last off the line. Unlike the year before, however, the big coupe wasn't in first place by the end of the lap, but still in the pits! A missing sponge turned up stuck in the throttle cable, and predictably, as Petoulet-"hen dropping," a nickname Maurice received after plowing through a poultry truck during an earlier tour of Reims-drove off he gave the offending cable a vicious workout, lapping as fast as the leading Ford hare. Once again the powerful Maserati began gobbling up the field like a whale moving through plankton, cheered on by an appreciative public. Sure enough, after the first hour Trintignant had gained 38 positions!

By six in the evening he was running in tenth, and with Simon at the wheel two hours later, the 151 reached seventh. Gaining on most and running without further serious problems, by 9:00 p.m. Colonel Simone's charge had made it into third, preceded only by the Surtees/Bandini 330P and Guichet/Vaccarella 275P-it was a remarkable performance.

All was going well until shortly after 10:00 p.m., when in rapid succession an alternator failure, boiling battery, and brake problems annihilated the effort, forcing 30 agonizing minutes in the pits. Resuming with Trintignant at the wheel, the 151 motored on until midnight, when it suffered a short circuit and was retired. Again Simone could only contemplate the ifs: Without the silly incident at the start his 151 would have led for the second year in a row, and without the last electrical peccadillo.... Well, in any case, the slippery new shape had yielded part of what it was designed for: The 151 had the best top speed of the field, an official 192 mph being seen far before the end of the Mulsanne Straight.

His determination unbroken, Simone entered s/n 002 in the Reims 12 Hours on 5 July 1964. Simon and Trintignant qualified eighth, splitting the Shelby Cobra coupes and beating all the 3-liter GTOs. The car retired with ignition problems, and DNF'd again at Montlhéry.

More changes were made the following winter, as the magazine Auto Italiana reported: "The car was...finished just days before the Le Mans April test days, with a 5-liter engine while a 5.2 was in final stages of preparation. We are in both cases dealing with...completely redesigned combustion chambers and intake (and) exhaust. A new item was a double ignition, a wary attempt to curb the dumb retirement cause of '64. The body included a smoother nose, higher wing arches and a larger rear window.... The chassis...was completely redesigned being made of a trellis.... The suspension this year will have independent wheels front and even rear whereas the '64 version included a de Dion axle. The car will weigh in at 950 kg. The brakes are hydraulic Girling discs and the wheels specially commissioned Borrani wires." This time Casner was to drive with compatriot Masten Gregory.

Once more, it appeared that the factory and Simone had gotten it all sorted out, particularly by dialing in even more power and, at long last, an independent rear suspension. But the optimism surrounding the car neglected to account for three important facts: First was the star-crossed history of the Tipo 151-Johnny Simone had been here before, and the results had always disappointed. The second problem was the rapidly advancing pace of Maserati's mid-engined opposition. By 1965, front-engined racers were distinctly disadvantaged. And third was the simple fact that motorsport is full of unpredictable tragedies. It was this third factor that would end the 151's story.

Our subject, now in white with French flag stripes, was scheduled for the Le Mans test day on 10 April 1965. It was a crisp, cool morning and, ironically, the Tipo 151 was for once in its life on schedule. After conferring with Bertocchi and Simone, Casner drove off from pit lane and, after a few slow warmup laps, set out on his first circuit at speed.

Like Icarus, at its highest moment the Maser became unglued, getting out of shape over the ominous rise toward the end of Hunaudieres and refusing to settle back down. Casner lost control at top speed, and the 151/3 slipped into a sickening barrel roll, left the track, and mowed down two trees before stopping. It was all over in seconds; both the driver and the car were beyond rescue.

Maurice Trintignant, as familiar with Le Mans as anyone, has a very strongly felt theory as to the cause of the crash: "The accident happened right after the big bump on the final portion of the Mulsanne Straight, where the 151 wanted to get all four wheels off the ground. With this car, you had to lift your foot off the throttle and gently kiss the brakes to sort of encourage the nose to stay low. But it was also essential to lift your foot off the throttle only partially, to keep the engine going. The American lifted his foot off completely, I think, and when the rear wheels were in the air, even though only for a tiny fraction of a second, the engine stalled, or almost stalled. That had the effect of a brake on the rear wheels when he landed, which put the car out of shape. Tragic.

"And it was the end for Maserati, too-a pity, because with the exception of the rear suspension, the car was perfect." In a cruel double irony, Casner's fatal accident occurred five days before the publication date of Auto Italiana's glowing review, and on the very stretch of road for which the 151 had been conceived.

That was it for the 151, but amazingly, Simone's singlemindedness came up with one last effort-an open mid-engined prototype, the Tipo 154 (also called Tipo 65) was built around the crashed car's engine in less than a month, according to marque expert Rob de la Rive Box. An illborn handful destined for Siffert and Neerpasch at Le Mans '65, it was a flash in the pan.

Thanks to Siffert's heroic dash at the flag the car got away quickly, but in trying to run with the leading Fords Jo crashed out on the third lap. That, at last, was that: Neither the Colonel nor Maserati would ever compete in the 24 Hours of Le Mans again. John Simone and his wife were tragically killed in a traffic accident two years later, and Maserati has yet to find another patron as faithful or as obstinate. It was a hard era-even for the strong.

Fifteen years later, the automotive world had changed beyond recognition-and consigned the 151s to obscurity. Thanks to one man's passion, however, the memory of 151/3 was ultimately resuscitated in a particularly complex way. As Jaguar has done with the XJ13 and Ferrari with its famous 125, the 151/3 has been re-created with as much originality as possible so that it might now be admired in the flesh.

This project began when the ever-helpful Peter Kaus, founder of the well-known Rosso Bianco museum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, decided to locate the surviving 151/1 and the remains of 151/3. There was virtually no trail to follow on these cars, but an initial meeting with Maserati's former boss, Adolfo Orsi, resulted in a few parts directly and a good start on the necessary information. Orsi also put Kaus on the trail of a spare 151 engine currently residing at the University of Bari.

The actual Casner crash engine is in the Tipo 154, which Kaus has as well. Feeding Kaus' desire to track down the remaining 151 pieces as quickly as possible was the fact that Maserati was junking ancient racing parts by the truckload at the time, literally to make room for the Biturbo era.

Eventually, with bushels of parts secured, Kaus managed-not without difficulty-to convince Maserati's new owner, Alejandro de Tomaso, to officially bless a remanufactured 151/3. With the factory's permission work at last began, the exterior coming from Modena's Allegretti, where the artisans were able to resurrect an original 151/3 body buck which had earlier been cut into pieces and thrown in a heap.

Meanwhile, as the chassis was being built in Germany, a discrepancy was found between the actual rear axle used and the one which Maserati's records had led Kaus to expect. Allegretti solved the mystery: Decades earlier, when the original Maserati axle proved too soft, the search for a better one led them to quietly buy a Jaguar unit!

Despite his Can-Am driving experience, Kaus found the finished Phoenix fearful to drive. "It was a rocket-very dangerous, and with a deafening oven for a cockpit. In fact, during a race on the old Nürburgring's small loop, it suddenly broke away, spun on and on, and wound up crushing the aluminum nose in the guardrail."

Finally concurring with history's verdict on the 151's rear suspension, today Peter is content to let the beast rest. It is now honorably displayed just 90 feet away from the 450S coupe that began the adventure.

Want more information? Search the web!

Search The Auto Channel!

|