The Pony Express

Michael Lamm recounts the development of Ford's 196 Mustang the first mid-engine throust toward Total Performance.

The Pony Express

Michael Lamm recounts the development of Ford's 196 Mustang the first mid-engine throust toward Total Performance.

Horse of a Different Color

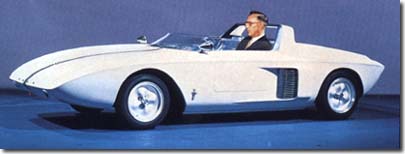

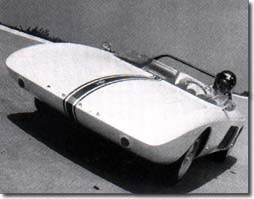

The Mustang I advanced quickly from concept sketches to package drawings conforming with the engineering specifications that were being laid down simultaneously. Najjar recalls that his studio's full-sized drawings contained the suggestion of a tubular spaceframe, and Ray Smith, the studio engineer, added the popup headlights, retractable license plate, fixed seats, and adjustable-reach steering and pedals.

The Mustang I advanced quickly from concept sketches to package drawings conforming with the engineering specifications that were being laid down simultaneously. Najjar recalls that his studio's full-sized drawings contained the suggestion of a tubular spaceframe, and Ray Smith, the studio engineer, added the popup headlights, retractable license plate, fixed seats, and adjustable-reach steering and pedals.

Trail Boss

Mixed Breed

The Fast Roundup

Put to the Whip

Old Paint

Want more information? Search the web!

Search The Auto Channel!