Though s/n 16407 would be sold to Jim McRoberts and Bill Nicholas, the competition urge remained. Whereas the previous effort had sponsorship backing, there would be none for 1979. "It was a blood and guts effort," Borri reflects. "To cut costs, we went with just two drivers, Tony Adamowicz and John Morton. I knew Morton from my SCCA days, and he was a very good driver and a humble man. We also decided to invite Otto Zipper to function as our team manager.

During practice in Florida, the press christened the immaculately prepared Morton-Adamowicz Daytona "a vintage racer," a viewpoint reaffirmed when three new factory-built 512 BB/LMs were unloaded: two for Charles Pozzi's team (s/n 26681 and 26685) and one for Luigi Chinetti and NART (s/n 26683). With swoopy, wind tunnel-designed "silhouette" bodywork an potent five-liter, flat 12-cylinder engines rated at 480 horsepower (some 80 more than the Daytona), despite tire troubles these Fiorano-tested bolides qualified high up in the starting grid while our heroes' front-engined dinosaur managed a meager 21th.

Adding insult to injury was the lack of comradeship they received from the Maranello's personnel tending to the sleek 512 Silhouettes. "Engineer Girotti was working with Pozzi's team," Borri recalls, tilting his head back for emphasis. "They were practically looking down their noses at us, like 'Who are these poor guys, running that old car?"' If anyone was depressed by the bad qualifying or lack of cooperation and respect, Zipper was the perfect tonic to keep the team's spirits high. As he reminded them

over dinner at a coffee shop near the track, Borri and crew had an immaculately prepared machine, and they already had firsthand top ten finishing experience at Daytona with this exact same Ferrari from the previous year. As the team downed their meal, Zipper mentioned he was "a bit tired" and wanted to turn in early. "Take these," roommate Borri said as he tossed the team manager the keys. "I'll bunk up with someone else." With that, Zipper got up from the table, said good night and ambled back to the Holiday Inn across the street.

Borri awakened the following morning shortly after six. Even though the green flag wouldn't drop for another nine hours, his mind was already racing: The pit area needed to be prepped and organized, the car had to have a final check, the spares would need one last scrutinizing-was anything else overlooked?

After showering, Borri went to wake Zipper. Several knocks on the door were greeted by silence. Knowing his friend's habits well he figured Zipper was obviously in the shower. Borri headed to the restaurant for a small breakfast and cup of coffee, returning shortly after seven. When Bruno's knocks were again greeted by silence he waved to the maid and asked her to unlock the door. Stepping into the room Borri was unprepared for what he found. Zipper lay in bed, motionless, his body rigidly curled up. "The instant I saw him," Borri recalls, "I knew he was dead."

Shock quickly spread through the team. With Zipper missing, the ship was sailing without its captain. A blanket of silence engulfed them, their minds reeling. As word spread through the pits the team came to a consensus: they would withdraw in honor of their departed friend.

As their conclusion was on the verge of being reached, NART impresario Luigi Chinetti walked over to express his condolences and to see if there was anything he could do. When told of their decision, Chinetti launched into an impassioned plea. "Withdrawing is the worst thing you can do," he emphasized. "Think about continue! The best thing to do is to race in his honor!"

Almost immediately, the crew's posture changed, a sense of purpose sweeping over them. Now galvanized with a common goal, they were united to press on. In the midst of the paroxysm, someone suggested laying a strip of black duct tape diagonally across the hood. They gathered around the old front-engined warrior for an impromptu ceremony. After the briefest of words, the Daytona had a new band of color.

With the decision made, Borri's main worry turned to the car's brakes. Always a weak link in the street Daytona, there was no major improvement for the track version. "The competition Daytonas used the standard rotors," Borri says. "While the calipers were thicker, the pads were the same size. We therefore planned to use three sets of pads-those at the start, and those installed during pit stops after eight and 16 hours."

After the green flag dropped, a bevy of Porsche 935s stormed off into the lead. The 512 Silhouettes were also fast, fluctuating between fifth and eighth in the first 70 laps. But disaster struck on the 75th lap. As the NART Boxer came off the high bank it blew a tire and slammed into the wall, eliminating it from the race. Although the driver was unhurt, the other two BBs were withdrawn-there had been a nearly identical accident in practice that had also been due to tire failure.

And so s/n 16407, the lone Ferrari, pressed on into the darkness. "At night is when you really feel the exhaustion," Fabbio says. "Around two in the morning you hit the wall, struggling to keep awake and alert. It was unbelievably cold, and we could barely talk because our voices were hoarse-we had to scream all the time to be heard over the constant roar of engines."

The team's "vintage racer 11 performed faultlessly through the night, save an oil hose problem. Borri recalls the driver noted the pressure dropping and pulled into the pits. After the hood was opened, they quickly determined the culprit: one of the lines was kinked. The car was wheeled into the garage, and the hose was replaced under the watch of a race steward.

Sunrise delivered the team's second wind: The higher the sun rose, the more confident they became. "Every time she passed," Fabbio smiles, 11 you could hear how perfectly she was running. The Porsches were dropping like flies, so we became more and more optimistic." As did the other Ferrari teams. With the Daytona now creeping deeper into the race's top five placings, Girotti and company's attitude changed: not only were they offering words of encouragement but seeing what they could do to help.

During the race's final hours, s/n 16407 lay in second place. Then, the lead Porsche developed trouble, obviously down on power and running poorly. It pitted, its mechanics a whirlwind of motion. The Daytona, a car whose era had come and gone, continued its surprising, troublefree sprint for the gold.

Though energy and optimism pulsated through the pits, Borri remained a bundle of frayed nerves. "He was constantly peppering us with questions," Fabbio smiles. "'Did you check the brakes?' 'What about tire wear and camber settings?' This made us work twice as hard. No one wanted to be the one who let Bruno and everyone else down."

Shortly before the race ended, the Interscope Porsche 935 limped out onto the track. With smoke pouring from its back, it took the checkered flag. A number of laps down, s/n 16407 streaked by in second place, the strongest-running car at the end.

Pandemonium erupted in the Ferrari pits, champagne flowed liberally, and the trophy was held high over innumerable celebrants' heads. It had been a journey from the dusk of shock and despair to the dawn of hope and final vindication. After the revelry subsided the pits were quickly dismantled, spares and tools packed, and all rushed to the airport to catch the six o'clock flight back home to California. Euphoric, yet exhausted, not a single crew member felt the plane lift off.

Want more information? Search the web!

Search The Auto Channel!

|

After six months, Borri moved to California when he met a fixture in the Southern California automotive scene, Otto Zipper. The well-known dealer offered more money and introduced Borri to the Ferrari world. Like Piper, Zipper also competed in Alfa Romeos, and his Borri-prepared GTAs captured their class at Daytona and the SCCA National Championship two years in a row.

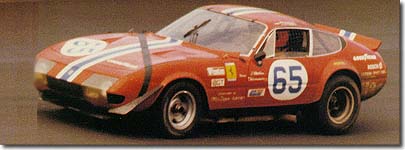

After six months, Borri moved to California when he met a fixture in the Southern California automotive scene, Otto Zipper. The well-known dealer offered more money and introduced Borri to the Ferrari world. Like Piper, Zipper also competed in Alfa Romeos, and his Borri-prepared GTAs captured their class at Daytona and the SCCA National Championship two years in a row.  At Carradine's request, s/n 16407 was quickly prepped for 1977's Daytona, where it did not start. It then competed at the 12 Hours of Sebring, finishing 10th. At the two races, "we saw what it took," Borri notes. "We decided to go for Daytona again, but this time with several months of preparation." This foresight yielded fruit, for s/n 16407 placed fifth overall in 1978.

At Carradine's request, s/n 16407 was quickly prepped for 1977's Daytona, where it did not start. It then competed at the 12 Hours of Sebring, finishing 10th. At the two races, "we saw what it took," Borri notes. "We decided to go for Daytona again, but this time with several months of preparation." This foresight yielded fruit, for s/n 16407 placed fifth overall in 1978.