![[The most important feature on your car is not an option.]](/images/sponsors/allstate/scale.gif)

![[The most important feature on your car is not an option.]](/images/sponsors/allstate/scale.gif)

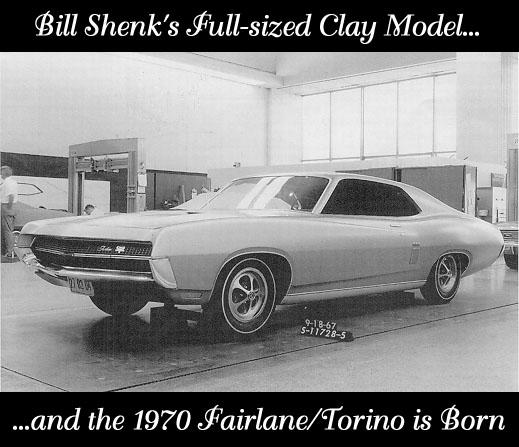

The Birth of the 1970 Ford Fairlane/Torino

by Bill Shenk

Taken from the May/June 1995 issue of The Fairlaner News,

the bi-monthly publication of The Fairlane Club of America.

This is the story of the 1970/71 Torino. The exterior design of

that model line started with me, and it ended with me. I was the

sole stylist for the design, and this is my story of what was and

what can "never be again."

You see, in 1967, several incidents occurred that placed me in

the right place at the right time. But let me back up for just a

moment. I had been a stylist with Ford since March 12, 1962.

Between that time and 1967, I was designing hub caps, wheel

covers, and 'C' pillar ornaments. In fact one of my 'C' pillar

circular ornaments ended up on the 1967 Falcon Futura. But

unknown to most people, that ornament was designed right after

lunch one Tuesday. The designing of that ornament began the

sequence of events leading to the 1970 Torino.

You see, I always brought my lunch to work, and I really liked

Oreo cookies. This particular Tuesday, my boss came over

immediately after lunch, and said that Joe Oros, director of Ford

exterior studio, wanted to go over all the design items for that

Friday. Since my boss had not given the Falcon ornament job out,

I got it. With 2 hours to make some type of design--anything for

the initial discussion was okay, just so long as it had lots of

pizzazz--I simply took this Oreo cookie I had not eaten, slid it

apart, and then sprayed the heck out of it with silver and flat

black Krylon. This was then dabbed with Klennex to really get a

chromed top look and the black to appear as "depth" of

detail.

Joe Oros asked about the ornament as a passing comment, assuming

it was all prepared. My boss piped in and also asked me where it

was. I pointed to the driver side of the 2-door Falcon roof area.

They walked over, and Joe just said, "That's the best

ornament I've seen. How did you make it in three

dimensions?"

Well, we talked several minutes, and then my boss asked the same

question so he could get Joe away from me and out of the studio.

I then simply went over to the car, took the ornament off, and

slowly snapped it in half. Joe flipped and did a double take at

both me and my boss. Then he said, "Make another one and we

show it, but for approval, not for direction." Smiling, Joe

walked out. My boss was astonished and was taken aback by my

solution to the problem.

I tell about this incident for several reasons. The most

important in that back in those styling days anything went, so

long as it could be built and looked different. Only one man had

the say on what went on a car, any car, from a Falcon to a Ford

Thunderbird, and that man was Joe Oros.

Several things happened to me soon after the Oreo incident.

First, I was promoted to senior designer. (I had the distinction

of having spent the shortest time ever as an "A"

Designer before being promoted to "Senior Designer."

Normally, a new hire coming directly from art center school spent

the first two years in one of four different design studios.

During this time he was evaluated by different directors for

"potential and styling ability." Today, this phrase is

called "problem solving creativity." If you made the

cut as a stylist, you were given the title of "B"

Illustrator, as I was in 1962. The promotion route was then to

"A" Illustrator, "B" Designer, "A"

Designer, and finally "Senior Designer." Even back

then, being promoted to Senior Designer in five years was just

not done.)

The second thing to happen occurred about two weeks after my

promotion--I was transferred to the Mercury Exterior Studio. I

later found out that the transfer occurred because the Mercury

director Buzz Grissinger had heard about the "Oreo

incident" and wanted me in his department. Soon after I

arrived, my immediate manager, Mr. Dardin, suffered a heart

attack and I took charge of department assignments. This is where

I found myself as the 1970 Torino and Montego were about to be

created. The process began with an assignment by Product Planning

about early April 1967 to begin work on coming up with a new

Montego. Ford was to also do a new Torino.

My design executive was Mr. Bob Koto--a splendid

and likable guy. He would create a scale model of what he felt

the new "this or that" should look like to grasp the

initial theme direction and to show his concept to Gene Bordinat.

This was always Bob Koto's method, and everyone accepted it as a

normal matter of business, including me.

My design executive was Mr. Bob Koto--a splendid

and likable guy. He would create a scale model of what he felt

the new "this or that" should look like to grasp the

initial theme direction and to show his concept to Gene Bordinat.

This was always Bob Koto's method, and everyone accepted it as a

normal matter of business, including me.

All of us were doing sketches and having real fun going

"way-out," stretching the design envelope. Most

sketches were comfortable, some stupid, some very well liked, and

some that we each fell in love with. My personal styling theme

had been the same for several years. I loved aircraft and had

gotten a job at Hughes Aircraft after running out of money for

more automobile designing art center school in 1957. I spent

three years with Hughes, mainly on "F-102" and

"F-106 Convair contract work. This was the era of "Area

Rule," "Compressibility," "Mach I," and

"Delta Wings." So some of my personal likes rubbed off

into my sketches at the Ford styling center, and Ford and Mercury

Exterior Studios.

During early 1967, I took it upon myself to create my own

personal list of directions to guide my sketches. Thus, I had a

personal design direction goal to work from. I used a

"SBB" (styling blackboard), which was a 7 foot high by

24 foot long vertical blackboard used for sketches, etc. There

were ten to fifteen of these large blackboards in the design

studios and these were always covered with each stylist's work.

With five to eight stylists in each department doing about five

to six rendering and sketches per day, the boards were covered by

the end of two weeks with every type and size, color and view, of

all sorts of car designs. We would have "design

reviews" internally with Buzz Grissinger, and select losers

and hopefuls. Then we would start all over again to reorganize

the board into types, shapes, model sizes, etc. All the while,

Bob Koto was still scale modeling his Montego on his walnut desk

in his private office. He did his thing, we did ours.

Several internal reviews later I had one (just one) sketch picked

out from over one hundred of mine which had a rakish front fender

line that disappeared into the door panel and a rear fender top

edge becoming the "wide hood" character. The top area

had a long, sloping, semi-fast backlite, and the plan view showed

off the "coke bottle" in and out form which gave the

squeeze on the area of the door (Corvair aircraft "area

rule"). I wanted length, but with some start and stop

flowing lines to the long bodyside. This, then, was the birth of

the "coke bottle" bodyside theme. Then Bob Koto told me

to do a Ford, not a Mercury.

I was given only four clay modelers to do an entire exterior.

This usually requires 12, sometimes more, but since other Mercury

programs were going on at the same time, and Bob Koto was the

boss, he told me that all I was working on was a

"back-up" full size model to show the brass another

Fairlane theme, and that his design was the "real"

Montego theme. I know then that I had no real sponsor for my

design, only a gesture of support because it was expected that

the Mercury studio would contribute to the Fairlane styling

competition. So I did my thing. I gave each modeler one job. One

had the front, back to the "B" pillar. One had

taillights to the "B" pillar. Another had the roof and

glass. And the final clayman had both rockers and lower bodyside.

I did the full size tape drawing, sections, and a scale model.

I also had a great resident engineer, Bob Volappi, who reinvented

the old body engineering solutions that continued to give my clay

the new solution uniqueness that Bob Koto could not understand,

even as it was happening. This was the first time an engineer

stayed after-hours to redefine the rules and Ford design

standards for wheel opening minimum requirements. That kind of

creative engineering was unheard of, particularly for a styling

department to propose new solutions for such things as wheel

clearances. This went for two-sided taillight optics, called

"concentric," as well. That's when both sides of the

red lens have an optic pattern, thus allowing the backcan to go

only half as deep into the trunk area. We found out later that

Planning and Marketing loved our new wheel openings as the new,

bigger F-70x15" tires could fit. Planning and Marketing

overruled Body Engineering that year, and many old and long

accepted engineering rules were changed by one engineer, four

clay modelers, and one senior designer.

I could go on and on, but the crowning touch was the very first

official show in the courtyard by the Product Planning people for

their boss, Lee Iacocca. You might recall that he was the Vice

President of Planning back then, and all approvals went through

him and Gene Bordinat. Well, since I had been told that my

efforts were only for backup support, and since I had been left

on my own, I made the decision to have my model di-noc done in a

straight shade of bright red. (Di-noc is a 54" high by 200

feet long, rolled up decal with hot water peel-off backing. Very

pliable, the clay modelers apply it by wetting the clay model,

then simply laying the di-noc on the clay and squeegeeing out the

all the water trapped between the two. It takes about 6 hours for

the di-noc to dry enough to be handled.) I should mention that of

the 12 full -sized clays seen by Lee Iacocca at that first

outside show, all of them except mine, the "back-up"

theme, were in silver di-noc. Nobody in the styling building

could believe that anyone would break the "silver di-noc

rule." The modeling is never sufficient for real good

surfaces, and besides, the unequal competition presented by an

unapproved color was a definite "no-no."

Thus started a very fast emotional ride for me.

We all peered through the tall, one-way, studio-to-courtyard

glass, and very slowly, after 15 to 20 minutes, the Millwrights,

who pull all the 15,000 pound full size clays, began to empty-out

the courtyard. After about 1 to 2 hours, there were only four

clays left--three silver and one red. The red went to the center

courtyard turntable. Lots of hands pointed here, there, words

were spoken (unheard by us), and slowly the last three silver

models were pulled out of the area.

I was beside myself! It was like a dream. I couldn't believe it.

The red car, the only one left, was mine. After another hour, the

red car was pulled back into the Mercury studio; very rapidly,

the studio filled with other stylists and many of the planners. I

had the model put back into the same "bridge for use"

where it was initially clayed. I was asked to move it into the

studio center bridge, but said no. I wanted it in the same bridge

because the points were already correctly established. I also

wanted the same modelers, and no more, to continue the work on

the model.

Bob Koto was beside himself and tried to persuade Buzz Grissinger

to let him take over the model, but he said no. Buzz was the

boss, and I knew he was my real boss. He simply came over and

said, "Fine job, but Bill, you know that for the next show

everyone will be after your car and after your design. I want

these doors locked at all times, and nobody but who You need

comes in, understood? Oh, by the way, the decision made today was

that the lead model will be the Ford Torino, so whatever you do,

this is now the Ford Torino, not the Mercury Montego." Then

Buzz walked out.

There were only three additional official shows for Lee Iacocca.

Never before, or since, have there been so few reviews of a car

at design center. Mr. Iacocca just fell in love with the design

and the color. He only said one thing to Gene Bordinat, "Go

back and tell Shenk, don't touch the car." This was passed

on to me, but when Buzz Grissinger relayed the same message I

said, "Great, but I will be touching the car." He

smiled, turned, and left.

I continued to touch, revising the taillight details, adding the

hide-away headlights we got from planning, adding slightly to the

plan curve, and sweetening the hood crown. I also added a new

hood for the "high series" and even worked out the

vinyl roof design. All this was done on this same red 2-door

hardtop clay model. The vinyl roof color had never been done on a

full size clay, but I did it, and in white. I also put a white

tape stripe on the red body. That was the configuration for the

fourth and final show.

And that is how it was back in 1967. The 1970 Torino grew out of

a combination of free-wheel styling, constrained time

requirements, and accidental occurrences that would never happen

again at Ford styling during the next 26 years I was there. I

retired in January 1993, after 31 years of drawing cars. Yes,

there were many other vehicles I designed, but this was the way

it was normally done. (Alas, never before and never again would

it happen.)

So, this is how one of our club Fairlane/Torino models was born.

I have written this article in hopes that all of us will continue

to find out more about the cars we own. Today, more and more, the

"real automobile" is rapidly disappearing, along with

it, as a statement of who we are. In its place are cars more like

simple appliances, to be discarded after 30,000 miles or 2 years,

whichever comes first. Keep looking around, call your club

friends, and continue to push the dial for "classic

cars." Maybe there will be a more from 1975 and on. Let's

hope so.

Postscript: Bill Shenk has two Rapid Transit vehicle patents, one

component patent, six exterior designs, three interior designs,

tons of sketches, and many beautiful renderings. Much of what he

had he has turned over to the Henry Ford Museum, Automobile

Archives Historical section. Edsel Ford II gave generously to

create this section many years ago. Since that time, many

designers from other companies, and management, have contributed

their works to the museum. This section of the museum is

dedicated to preserving the documents related to the automobile

for all to share. Bill Shenk's biography is (or soon will be) in

the library for any and all to come in and read.

Copyright © 1997 The Auto Channel.

Send questions, comments, and suggestions to

Editor-in-Chief@theautochannel.com