One Man's Star Ship

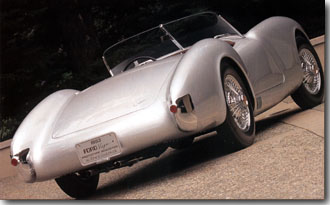

Vince Gardner's Ford Vega shoulda been a contenda.

One Man's Star Ship

Vince Gardner's Ford Vega shoulda been a contenda.

According to Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg historian Josh Malks, "Vince was highly creative and enthusiastic but a difficult person to work with. Nevertheless, when Buehrig moved from Auburn to Budd (a Detroit-based car body manufacturer) in 1936, he took Gardner with him. Years later, the two went to Studebaker, then to Ford together." At Raymond Loewy Associates' South Bend, Indiana studio, Buehrig and Gardner were instrumental in Studebaker's emergence as the industry's design leader after World War II.

According to Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg historian Josh Malks, "Vince was highly creative and enthusiastic but a difficult person to work with. Nevertheless, when Buehrig moved from Auburn to Budd (a Detroit-based car body manufacturer) in 1936, he took Gardner with him. Years later, the two went to Studebaker, then to Ford together." At Raymond Loewy Associates' South Bend, Indiana studio, Buehrig and Gardner were instrumental in Studebaker's emergence as the industry's design leader after World War II.  To seal the bargain, Motor Trend published a photo of the check-presentation ritual: A dapper Vince Gardner in a well-tailored suit shaking hands with stylist Willys Wagner of Ford's International Division while chief-contest-judge Frank Kurtis smiled approvingly. Attorneys clutching legally binding contracts were notably absent.

To seal the bargain, Motor Trend published a photo of the check-presentation ritual: A dapper Vince Gardner in a well-tailored suit shaking hands with stylist Willys Wagner of Ford's International Division while chief-contest-judge Frank Kurtis smiled approvingly. Attorneys clutching legally binding contracts were notably absent.  That never happened partly because the Ford Motor Company took an interest in the Vega and summoned it back to Dearborn to help celebrate the firm's 50th anniversary. While in Detroit, Gardner dropped in to visit fellow stylists at GM. Dave Holls, who began designing Cadillacs in 1952, recalls the day the Vega appeared. "Every designer in the place was immediately drawn to the windows. Five minutes later, the studios were empty and everyone was down in the parking lot looking at Gardner's Vega. It was such a pure statement. We all thought it was just an exquisite little American sports car. Interestingly enough, the small team working on the Corvette at the time were buried so deeply in the styling building that they missed seeing the car."

That never happened partly because the Ford Motor Company took an interest in the Vega and summoned it back to Dearborn to help celebrate the firm's 50th anniversary. While in Detroit, Gardner dropped in to visit fellow stylists at GM. Dave Holls, who began designing Cadillacs in 1952, recalls the day the Vega appeared. "Every designer in the place was immediately drawn to the windows. Five minutes later, the studios were empty and everyone was down in the parking lot looking at Gardner's Vega. It was such a pure statement. We all thought it was just an exquisite little American sports car. Interestingly enough, the small team working on the Corvette at the time were buried so deeply in the styling building that they missed seeing the car."

|

| |||||||||||

Copyright © 1996, 1997, 1998 The Auto Channel.

Send questions, comments, and suggestions to

Editor-in-Chief@theautochannel.com