The Price Per Gallon - Why? Who? When?

Editors Note: Because most of you buy their fuel at a convenience store I though you would like to read their take on why a gallon of gas costs what it does.

Washington DC; The NACS Fuel Report: Retail gasoline prices are among the most recognizable price points in American commerce. And with good reason: Gasoline purchases account for approximately 5% of consumer spending. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that the average U.S. household will spend about $2,000 for gasoline in 2015.At the same time, gas prices are among the least understood prices in the country because they often appear to increase or decrease without much reason. Here is a primer on what goes into the price of a gallon of gasoline, and what causes prices to go up or down and vary from store to store.

Ownership and Supply

Arrangements

Unlike a few decades ago, when the major oil

companies owned and operated a significant percentage of retail fueling

locations, less than 0.4% of all convenience stores selling fuels today are

owned by one of the major oil companies. About another 4% are owned by a

refining company. Instead, the vast majority — about 95% of stores

— are owned by independent companies, whether one-store operators or

regional chains. Each of these companies has different strategies and/or

strengths in operations, which can dictate the type of fuel that they buy

and how they sell it.

There are four broad factors that can impact retail prices:

- Fuel type: Typically, stores that sell fuel under the brand name of a refiner pay a premium for that fuel, which covers marketing support and signage, as well as the proprietary fuel’s additive package. These branded stores also tend to face less wholesale price volatility when there are supply disruptions.

- Delivery method: Retailers who purchase fuels via “dealer tank wagon” have the fuel delivered directly to the station by the refiner. They may pay a higher price than those who receive their fuels at “the rack” or terminal. In addition, a retailer may contract with a jobber to deliver the fuel to his stations or operate his own trucks – the choice will influence his overall cost.

- Length of contract: Even if they sell unbranded fuels, retailers may have long-term contracts with a specific refiner. The length of the contract — which can be 10 years, sometimes longer — and associated terms of that contract can affect the price that retailers pay for fuels.

- Volume: As in virtually every other business, retailers may get a better deal based on the amount of fuels that they purchase, whether based on volume per store or total number of stores.

Even within a specific company, stores may not each have the same arrangements, since companies often sell multiple brands of fuels, especially if they have acquired sites with existing supply contracts.

Crude Oil’s Affect on Gas

Prices

No matter who owns the station, retail fuels prices are

ultimately affected by four sets of costs: crude oil costs, taxes, refining

costs and distribution and marketing (which accounts for all costs after

the fuel leaves the refinery).

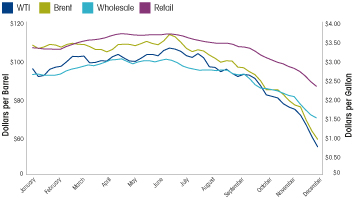

Crude oil prices have by far the biggest effect on retail prices. Crude oil costs are responsible for about two-thirds of the cost of a gallon of gasoline. In 2014, crude oil costs were 65% of the retail price of gasoline. While there may be slight variations in the costs of refining or distributing and retailing fuels, crude oil prices can experience huge swings.

Given there are 42 gallons in a barrel, a rough calculation is that retail prices ultimately move approximately 2.4 cents per gallon for every $1 change in the price of a barrel of crude oil. While this is not an exact calculation and ignores a variety of influencing factors, it helps demonstrate that as crude prices change, so does the price of retail gasoline.

Taxes are largely per gallon, although some areas have sales taxes on fuels, and those taxes increase as the price increases. There sometimes are significant tax disparities between stations located in the same market area but in different cities, countries or states. For instance, New Jersey has a gasoline tax of 32.9 cents per gallon, while neighboring Pennsylvania’s gas tax is 68.9 cents per gallon.

Sales Strategies Impact Gas

Prices

Fuel retailers face the same question that all retailers

face: sell at a low profit per unit and make up for it on volume, or sell

at a higher profit per unit and expect less volume?

But there also are several considerations in setting fuel prices that retailers of other products don’t face.

- Wholesale price changes: Competing retailers in a given area may have very different wholesale prices based on when they purchased their fuel, especially during times of extreme price volatility. Gasoline is a commodity, and its wholesale price can have wild swings. It’s not unusual to see wholesale price swings of 10 cents or more in a given day. Depending on sales volumes and storage capacity, retailers get as many as three deliveries a day or as few as one delivery every three days or so. Due to competition for consumers, retailers may not be able to adjust their prices in response to an increase in wholesale prices because their competition may not have incurred a similar increase in their cost of goods sold. Conversely, a retailer may adjust his prices when the competition adjusts prices, either following or in advance of a shipment.

- Contracts: How retailers buy fuel can play a significant role in pricing strategy. Retailers sign long-term contracts (10 years is the norm) and these contracts may dictate the amount and frequency of their shipments. When supplies are tight, retailers with long-term contracts may have lower wholesale costs than retailers who compete for a limited supply on the open market, but they may also face allocations (a maximum amount of fuel that they may obtain) on the amount of fuel they receive.

- Brand: Who retailers buy fuel from also affects pricing strategies. Branded retailers often pay a premium for fuel in exchange for marketing support, imaging and other benefits. Branded retailers typically have the least choice in how they obtain fuel, or at what price, but that is offset by the many benefits that a brand provides.

Each of these factors adds complexity to a retailer’s pricing strategy, and they can create unusual market dynamics. There are times when the retailer with the highest posted price in a given area actually may be making the least per gallon, based on when, how and where the fuel was purchased.

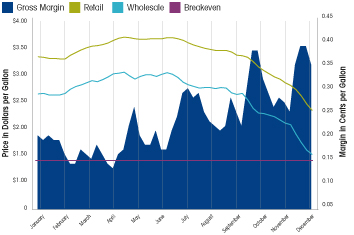

No matter what their pricing strategy, retailers tend to reduce their markup to remain competitive with nearby stores when their wholesale gas prices increase. This can lead to a several-day lag from the time wholesale prices rise until retail prices rise. Likewise, when wholesale gas prices decrease, retailers may be able to extend their markup and recover lost profits, with retail gas prices dropping slower than wholesale prices.

Despite extreme volatility, retail margins for fuel are fairly consistent on an annual basis. Over the past five years, the annual average retail mark-up (the difference between retail price and wholesale cost) has averaged 18.9 cents per gallon. Ultimately, retailers set a price that best balances their need to cover their costs with the need to remain competitive and attract consumers, who are very price sensitive and will shop somewhere else for a difference of a few cents per gallon.

Retail Profitability Measured Over

Time

The pattern of retail profitability is the opposite of what

most consumers think. Due to the volatility in the wholesale price of

gasoline and the competitive structure of the market, fuel retailers

typically see profitability decrease as prices rise, and increase when

prices fall. On average, it costs a retailer about 12 to 16 cents to sell a

gallon of gasoline. Using the five-year average markup of 18.9 cents, the

typical retailer averages about 3 to 5 cents per gallon in profit.

(Retailer costs to sell fuel include credit card fees, utilities, rent and

amortization of equipment.)

Over the course of a year, retail profits (or even losses) on fuels can vary wildly. In some cases, a few great weeks can make up for an otherwise dreadful year — or vice versa.

With its extreme volatility, fuels retailing is not for the faint of heart — or for those with limited access to capital. Perhaps that is why that since 1994, while overall fuels demand in the United States has increased, the total number of fueling locations (all convenience stores selling fuel, plus gas-only stations, grocery stores selling fuel, marinas, etc.) has decreased from more than 200,000 to a little more than 150,000 sites.