The Auto Channel Feature Story

HENRY KAISER: POSTWAR PIONEER-PART 1

by Bob Hagin

SEE ALSO KAISER AUTOS: PART 2

June 27, 1997

"He was a nice old guy and seemed to really enjoy watering his own lawn on summer evenings. He also astounded all of us neighbors when he'd give house tours and comment that he had telephone extensions in his bathrooms."

These were my wife Carole's pre-teen impressions of her Lafayette,

Calif. neighbor, Henry John Kaiser. Carole recalls Kaiser as "...a nice

old guy.." while historians remember him as the World War II

industrialist who revolutionized ship building and was a pivotal player

in America's wartime economy.

But automotive historians regard Kaiser as the visionary car builder who almost shouldered his way into the "good old boy" club of American auto manufacturers when the war ended.

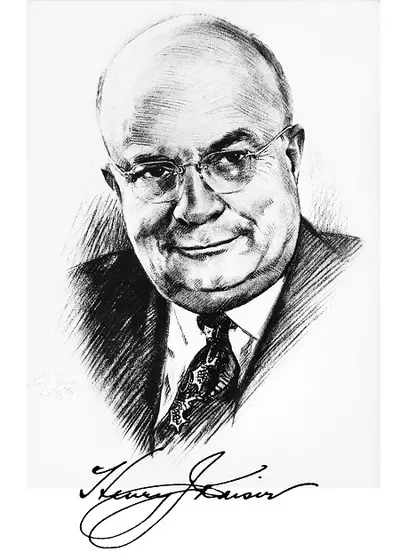

Henry J. Kaiser was the classic American success story. Born in New York State to German immigrant parents in 1882, he left school at 13 to work and help support the family. His rise through the ranks of American business started with menial work in a dry goods store and progressed to the point where he was building ships and dams, highways and high rises.

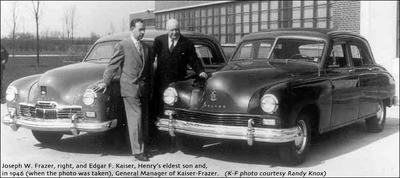

Then when the war ended and the American public turned its attention to consumer goods, Kaiser decided to get into the auto making business. He had been intrigued with the idea since the early '40s and even during the war years made plans to capitalize on the pent-up new car desire that Americans were sure to experience after five years of automotive austerity. But for all his business acumen and daring, he realized that entering into the American automotive arena would require the expertise and contacts of a Detroit insider. To remedy this, Kaiser went into partnership with Joseph Washington Frazer, a Detroit denizen who was definitely an insider.

Unlike Kaiser, Frazer was born into an upper-middle class family that could indulge him in his whim of dropping out of Yale for the grind of a laborer's job at the Packard factory in 1912. He later sold Packards at his brother's dealership and owned his own Packard store before World War I. After the war, he climbed the corporate ladder at General Motors and became assistant treasurer of GM Acceptance Corporation. He progressed through a vice-presidency at Chrysler, and after taking control of the failing Willys-Overland auto company in 1938, turned that organization around to where it showed a profit during the last years of The Great Depression. Frazer seemed heaven-sent for a partnership with the dynamic Kaiser, even though Frazer had publicly labeled his future partner as "half-baked" and "stupid" in 1942.

As the war ended, Frazer dreamed of building a new car that would carry his own name but in spite of his connections and business savvy, he was unsuccessful in raising money from Eastern banks. He headed for California to try his luck with the more adventurous banking houses of the West.

A.P. Giananni, founder of the Bank of America, was a primary banker for the various Kaiser industries and when Frazer came to him to seek funding for his venture, Giananni suggested that Kaiser and Frazer join forces: Kaiser entering into the association by virtue of a seemingly unlimited supply of capital and enthusiasm with Frazer supplying his automotive talent and contacts. Two weeks later, in July of 1945, the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation was registered in Nevada.

From the onset, the corporation made mistakes that both men should have recognized and avoided. The company went public and the initial stock offering sold out immediately, and although it brought in $54 million, Kaiser later acknowledged that he should and could have solicited three or four times that amount.

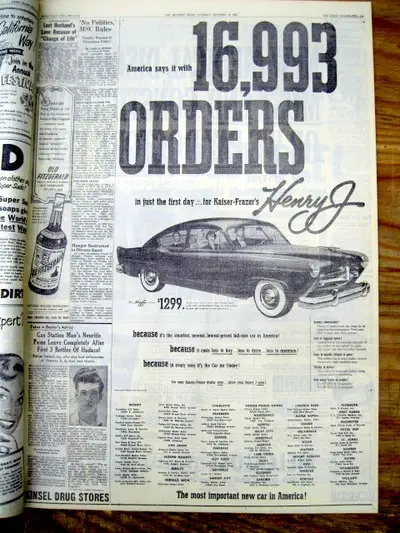

Being the expansive type, Kaiser negotiated the lease of a gigantic former wartime factory at Willow Run just west of Detroit. He wanted to produce a $500 "people's car" - a modern Model T - with a small engine and front-wheel drive. He was quick to learn from his partner that if his Kaiser-Frazer vehicles were to challenge The Big Three (Ford, GM, Chrysler) or even the established independents like Hudson, Studebaker and Nash, his company would have to go mainstream with a conventional six-seater sedan that was modern enough to draw brand-loyal customers away from the established brands. This he did and within a few years of its inception, Kaiser-Frazer automobiles were the fourth best-selling brand in the U.S.

After reading the various biographies of Henry J. Kaiser and talking to people who had worked for him, I get the feeling that the man enjoyed the thrill of business as long as he could do it his own way. He was impatient with the shortcomings of others and the "established" way of doing things. In part two of this story, we'll examine how Kaiser's insistence on building and marketing his vehicles without regard to conventional thinking (as well as a fair amount of bad timing and even worse luck) lead to the descent and final demise of the most successful and meteoric independent American auto maker in contemporary automotive history.